Engaging in Artificial Intelligence and machine learning

Alexandra Canet-Font reviews four different approaches to public engagement with AI and reflects on the need to ensure its human-centred development.

Estimated reading time: 20 minutes

What does Public Engagement of Artificial Intelligence might look like? What perceptions are we handling? Artificial intelligence is a complex subject, which more often than not, happens within a black box. Lest we forget that most of the research in this discipline is carried out by transnational companies, whose ultimate aim is to see the public as users, and not as co producers. We, as communicators, have a real challenge before us. In this article, Alexandra Canet reviews four different approaches to public engagement with AI and reflects on the need to ensure its human-centred development.

A recent global survey by Pew Research has shown that the acceptance of Artificial Intelligence is higher in young educated males. The lower the level of education, the lower the acceptance, which is not surprising taking into account that automation is affecting those with lower skilled jobs. A special eurobarometer issued in 2017, looked into the attitudes towards the impact of digitisation and automation on daily life and concluded that perceptions of robots and artificial intelligence are generally positive. Once again, the report stated that this depended greatly on the level of education and job roles. Furthermore, respondents expressed widespread concerns that the use of robots and artificial intelligence leads to job losses and the need to carefully manage technologies.

In a recent chat I had with Virginie Uhlman, research group leader at the European Bioinformatics Institute in Cambridge (dependent of the European Molecular Biology Laboratory), she feels the conversation needs to move more from the perils of the AI in the future, to the perils this technology poses today, and she frames it in an interesting way: not so much focusing on its intelligence, but, actually, on its lack of it. “The vast majority of the AI that is out there is essentially pattern matching but even though I think it makes sense to brace ourselves and the public to understand the possible challenges of automation in the future, we need to be aware that nowadays, everyday AI that is impacting users is, in essence, not very intelligent. There are many biases ingrained in this technology, it is not fully effective yet, and I think it is important we communicate this properly,” says Virginie.

In a 2021 paper, a group of researchers from Google and Ipsos surveyed public opinion of artificial intelligence with 10,005 respondents spanning eight countries across six continents. They focused on issues such as expected impacts of AI, sentiment towards AI, and variation in response by country. They identified four groups of sentiment towards this technology (Exciting, Useful, Worrying, and Futuristic) whose prevalence distinguished different countries’ perception of AI.

What does this sentiment analysis tell us? That there are people feeling worried (worrying), others that see it as something to look forward to (exciting, futuristic), and others, that it might have an application (useful). It is an interesting mix, which I myself have encountered multiple times when working in the dissemination of this discipline. The fact that, in the paper, the majority of respondents marked that AI would be “either good or bad for society, depending on what happens,” I thought was highly revealing. There is a call to action in this phrase, and that “what happens” can either be shaped by those developing the technology, or all of us, as a society. For the latter, we need to have a real dialogue - effective public engagement of AI. So, what does Public Engagement of Artificial Intelligence might look like? Or, better yet, what does it not look like?

In a paper from 2020, David Robb, from Heriot-Watt University in Edinburgh and colleagues, designed a public engagement activity and surveyed perceptions before and after the activity. They designed a light touch survey instrument integrated with the engagement activity to probe public knowledge and opinions about the future of Robotics and AI, in the context of extreme environments. What did they find out? That exposure to the exhibit did not significantly change visitors’ immediate knowledge and only slightly moved opinion. The paper was presented at the 2020 IEEE International Conference on human - robot interactions and I believe it is significant as it is telling us that, even though the event reached out to a couple of hundred people, it did not improve or allow those people to explore this technology or understand its applications - it didn’t seem to change perceptions.

Colin Garvey, a postdoctoral fellow with Stanford University's Institute for Human-centred Artificial Intelligence in a letter to the editor of the Journal of Integrative Biology states that the Artificial Intelligence community’s orientation toward public and news media engagement is key to the effective design of public engagement in AI science. In his own words: when AI scientists explain away public concerns about AI as the irrational response of misinformed people (e.g., fear of the Terminator stoked by a sensationalist media), they reproduce the ‘‘deficit model’’ of the public’s understanding of science. According to Garvey, this unchecked belief poses a potential barrier to broader public engagement and the democratisation of AI, and I couldn’t agree with him more.

How can we move away from this looking down to our audiences? What other ways can we find to engage in this complex discipline, that might enable different communities to understand what this science can mean for them in the future? What Garvey critiques in his letter to the editor is essentially the top-down approach to public engagement of Artificial Intelligence we are so used to seeing.

Artificial Intelligence as the visitor, not the exhibition

What if we stopped viewing Artificial Intelligence as the product or the object of study, and turned it into the spectator?

What if we stopped viewing Artificial Intelligence as the product or the object of study, and turned it into the spectator? Can we use the learning properties of Artificial Intelligence and its peculiar way of perceiving the human world to create an approach which is accessible and innovative? This is what Matteo Merzagora, director of TRACES, has been delving into. He and his team have been exploring how to empower people to live with artificial intelligence, to interpret critically its presence and thus see if this helps them decide how and when to best make use of the technology. “We want to inspire and enlarge the view about how you can talk about artificial intelligence”, Matteo states, “and we do it by placing AI as co-spectators of our human cultural productions”. They produced science engagement activities not about AI, or using AI, but for AI.

There are many scenarios in which algorithms are now the target audience of human work. “If I post a text or my comments on Facebook, the first reader is going to be an algorithm that will check that what I’m saying is not hate speech, for example”, says Matteo. In fact, as he pointed out, there were already people out there creating content to trick algorithms, either on youtube or hacking a smartphone, so, why not explore this idea? Why don’t we try to see this as a means to produce cultural productions for artificial intelligence? Their work saw AI as a target group of culture, giving participants the ability to understand how this technology could interpret the world around them, especially something so complex, and intrinsically human, as is culture.

A very simple idea, but which gives users a sense of what an algorithm can or cannot do. Settings were informal, the technology, accessible. The project’s aim was also to showcase how, actually, AI is at the service of the user, leaving behind popular claims about the superiority of this technology. They wrote plays specifically for the project, and participants then visualized them with different AI systems, like a smartphone translator app or Google lens. The outcomes were interesting and sometimes unexpected - the Google lens kept telling the users what clothes the actors were wearing and where to buy them, for example. The experience was repeated asking visitors to accompany an IA to visit a science festival (Turfu, in Caen) or an art exhibition (ARTEX, in Paris).

The two key elements of this project were accessibility and interactivity. Firstly, the apps that were used were free to download, it was an AI in your pocket approach. Secondly, the TRACES team wanted to put interactivity first, giving life to the technology, and an active role to users. Their aim was to understand how we, as users, relate to the technology, which according to the TRACES team, can be more useful in our day to day lives than to understand the science behind it.

The initiative “IA spectatrices”, embedded in the European project SISCODE, had the aim of creating a protocol on how to observe the world alongside artificial intelligence, to better understand artificial intelligence and our relationship to it. “The main outcome of our experimental project is to help other museums, researchers in AI and policymakers to widen the type of outreach activities they are putting forward,” says Matteo.

Not the what, but the whom

With a different angle, there is now a strong movement to focus on the who instead of the what when it comes to Artificial Intelligence. The reason behind this is to provide role models in the world of programming and data science. Nicole Wheeler, a data scientist at the University of Birmingham, has been working on public engagement of her work for several years now, and the greatest challenge she has faced is around people’s beliefs - not in AI - but about who develops AI. “I want to challenge the assumption that you need to really enjoy sitting at a computer all day, doing lots of maths and not necessarily communicating with people and interacting with the real world or creating applications that can’t really help us improve as a society”. Her aim: to demystify careers in computer science and bring more female role models into the classrooms.

There is a real gap between the skills that students think they're leaving school with and the skills that employers want

Nicole’s work was triggered by the UK digital skills gap report, in which there is growing recognition that digital skills are key, but that there is a real gap between the skills that students think they're leaving school with and the skills that employers want. Furthermore, the report states that the digital skills gap is substantially bigger for girls than boys.

In early 2021, Nicole, along with the all-girls Wimbledon High School and the girls’ day school trust, launched the AI in Schools programme. This four week program was designed for year eight students. Students had to gather data around a social problem they were interested in and then build and test machine learning tools. “The students had to see what insights they could draw from their AI analysis. We then reflected on the strengths and weaknesses of using AI as well as what they can do with those insights and what the real world actions would be,” she explains.

“I wanted to show there are many people, like myself, who are not only developing algorithms to sell shoes, but, actually, are working on real world issues, such as my work in infectious diseases,” Nicole states. In our conversation, Nicole also identified a challenge I thought was most relevant: When it comes to Artificial Intelligence, most of the learning materials are simplified, almost toy based representations of AI. “In AI in schools, we want to get them working with real data, which is a lot messier than a lot of students expect and have a lot of unexpected challenges that come with it.”

Attitudes towards Artificial Intelligence

The AI Ethics forum, a project organised by the Computer Vision Center (CVC) and funded by the Fundacio La Caixa, which I had the opportunity to organise in 2019 in Barcelona, brought together a set of working groups with neighbours from the city and researchers in the topic at hand. We had the mission of talking about the application of Artificial intelligence in five big topics: Autonomous driving, personalised medicine, digital humanities, social networks and education. The project was organised by myself, my then colleague Nuria Martinez Segura, Communications Officer at the Computer Vision Center and Sílvia Puente, Associate Professor at the Department of Education and Social Pedagogy at the Autonomous University of Barcelona.

The forum followed a classic approach to citizen engagement: five closed seminars in which researchers had the opportunity to talk to attendees about the advances on each of the identified topics. After each seminar, there was a focus group that looked into the worries, doubts and needs of those present, most of them with a non-technical background. We paid all participants for their time, as we acknowledged they were providing us with a service.

How do we make sure that the next generations are prepared for an automated future?

The main outcomes of the project showed that common to all five focus groups we had worked with (each focus group had different participants) there was one outstanding issue: who is going to be left behind? Participants thought it was fantastic that we have technology which will improve our lives, and there was relative worry about data management and legislation, but the outstanding concern was always - how do we make sure that the next generations are prepared for an automated future? and what is the role of society in making sure this happens?

The concerns that emerged in these focus groups were collated and transformed into a set of questions that were then posed to a panel of experts in public debates. We had professionals from different sectors in each of the seven debates: academia, third sector, philosophy and public sector. In total, we had 46 people participating in the focus groups, 93 people participating in the seminars, 30 panelists and 460 people attending the public debates. A six-month project in which we gathered the perception of non-technical audiences and third sector associations about computer vision and Artificial Intelligence and the possible answers to those concerns by experts in the field. The next step? Feeding the main outcomes to the local authorities and implementing the needs identified in the project. Easier said than done.

Involving our audiences deeper: the role of living labs in Artificial Intelligence

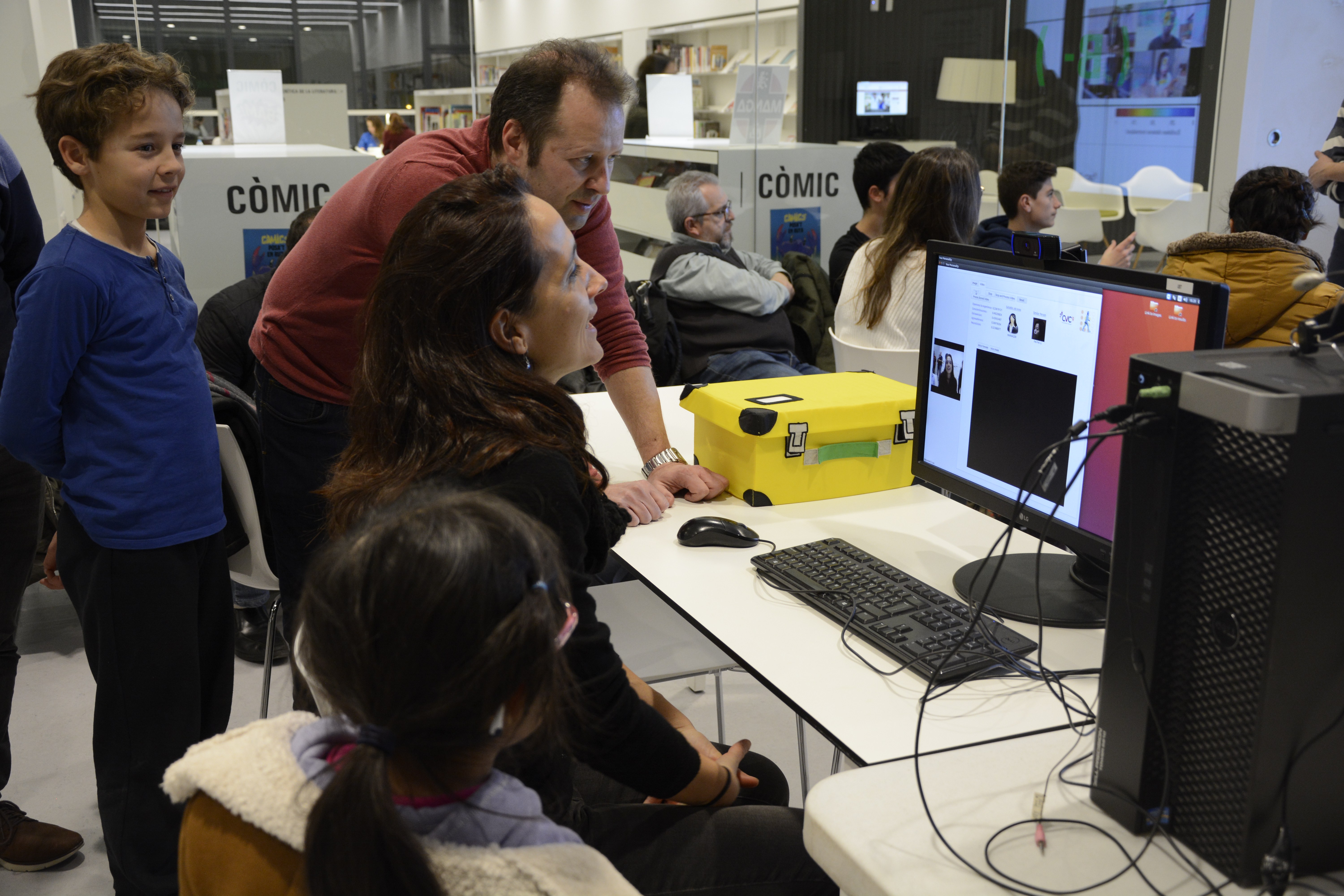

"When we talk about citizen engagement, I have heard many, many times - but how do we engage citizens? This is a top down approach to the problem, right? In our case, we already had citizens engaged because libraries are a space where people usually go to - from all backgrounds and education levels. This is unique, and very powerful.” Fernando Vilariño, co-lead of the Library Living Lab, CVC deputy director and professor at the Autonomous University of Barcelona, has been working on the development of a living lab in a public library in Barcelona for the past eight years. The aim: to understand how technology can transform the cultural experience of people with public libraries at its heart.

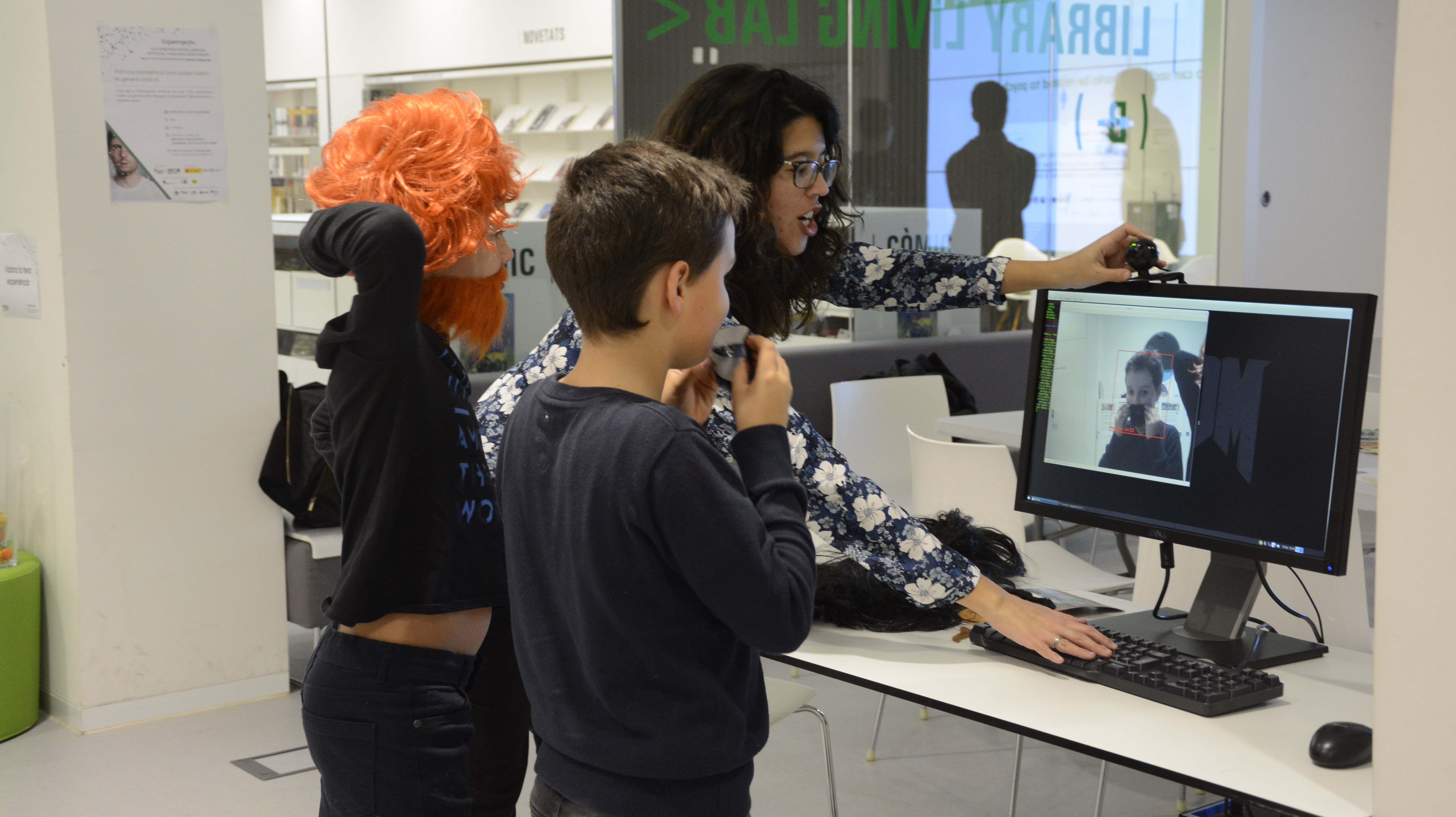

One of the key actions in regards to Artificial Intelligence that took place at the Library Living Lab was the project ExperimentAI, which gathered more than 200 people in 2019 and was produced along with researchers in Computer Vision and Artificial Intelligence, the activities and prototypes stemming from the core technology these researchers were developing. The immersive experiences touched upon real life applications such as autonomous driving, digital health, facial recognition or document analysis. The project was organised by the CVC and funded by the Spanish Foundation for Science and Technology, a public foundation under the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation and using the library as the project’s venue was key to bringing in participants and creating a public debate among the potential users of this technology.

The aim was not only to put in contact researchers and final users, but also other stakeholders such as public administration and industry in this living lab approach. “From my perspective, the best result of ExperimentAI was that it was a dive into the potential futures Artificial Intelligence opens up for us. The public spaces - the public libraries - act as the connector of the different stakeholders,” says Fernando. The activity attracted medical specialists, neighbours, children, retailers or psychologists - people with different backgrounds stepping through the door, wanting to talk about the applications of the technology showcased. As Fernando sees it, we cannot assume that we are going to draw artificial intelligence in our cities and in our communities without the actual implication of the people that are going to play a role in their deployment.

The Library Living Lab project is now in a scalability phase, working together with more than 240 libraries in the area of Barcelona. The objective is to create a network that will share a common programme, called Bibliolab, an evolution of public libraries in which technology is in every factor. As Fernando sees it: “Public libraries are changing their role and way of thinking - they are transforming into knowledge hubs. This is exactly what I experienced in ExperimentAI, citizen engagement within our valued and trusted public spaces.”

The living lab approach can be applied to many locations, applications and technologies. DFKI, the German Research Center for Artificial Intelligence, has been exploiting it as a model to involve key users in the development of their technologies since 2005, in an effort to engage participants in the development from the outset. DFKI has a number of living labs scattered throughout Germany, each one with a different application focus. They started a technology café, in which they’d invite potential users of their AI technology into focus groups, gathering their thoughts, ideas and perceptions of the technology that would be used in assisting them in the future.

DFKI have eight living labs in total, which have been visited by more than 8,000 people, touching on topics such as assisted driving, smart factories or smart working spaces. The Bremen Ambient Assisted Living Lab, for example, focuses on assisted living. The involvement of the potential users of this technology from an early development phase is crucial in order to develop technologies that will effectively serve the user. This lab in particular is an apparently normal apartment which has been equipped with the technology DFKI’s laboratories are developing to help assist people with caring needs. “We aim to answer, what kind of technology is useful? But we answer it along with those who need it. We invite them to come, to tell us their thoughts, to try out the technology and to understand how it behaves. They are helping us get solutions that will actually benefit them, instead of us trying to play a guessing game,” says Reinhard Karger, spokesman for DFKI.

In fact, DFKI have a long tradition of involving the public with their work in Artificial Intelligence. Back in the nineties, Reinhard helped develop what they called “the verbmobil,” a machine that was constructed as a prototype aimed at non-technical audiences and which processed speech, the early days of today’s Siri or Alexa. In Reinhard’s words, they aimed to show the science facts and not the science fiction, by building something specific in which both the software and the hardware were comprehensible for anyone who would look at it. At that time, it was important to show that the machine was able to process a complex problem, and to showcase the steps it took in order to achieve it.

Moving forward

Involving different audiences into our science is proving to change, not only the way they see Artificial Intelligence, but also how researchers envision their own work. For Nicole Wheeler, for example, her work in public engagement is a good accountability tool. For Reinhard Kerger, it has been the way to stop playing a guessing game and making informed decisions. For Virginie Uhlmann it has meant changing the way she views her own research.

I have no answer as to what effective public engagement of AI looks like. However, I do feel there are some interesting avenues to explore. Shifting the focus from the participant and onto the technology, how the TRACES team have done, can be a different approach to it. Making sure that the technology used is open, and accessible, ready to use in our own pockets. Opening up public spaces, such as libraries, hospitals or our city centres, taking the conversation to spaces we all share, value and respect.

Building prototypes which are specific for non technical audiences, taking the time and effort to work on explainable AI which will let professionals know why the algorithm has reached a specific conclusion. Making sure we are bringing diverse models into schools and festivals, to ensure we open up a job niche which is currently small and predominantly male, and last but not least having an honest conversation on the challenges this technology poses today, as opposed to the future.

However, all of this is costly and needs solid institutional support. We need research institutes to give public engagement the importance it really has and weave it into their long term strategies as a priority. Without this support, public engagement of AI has no future, thus putting into risk a whole portion of society who might not be able to keep up with the rapid changes and a society which might, tomorrow, give AI the cold shoulder.