How librarians went from being possessors to acting as custodians - and how it can inspire us

| Estimated reading time: 17 minutes

The first half of the twentieth century saw the omnipotence of libraries over the world of information and the organisation of knowledge. But in the following fifty years, many libraries failed to understand and adapt to the new demands of their public, spending endless time cataloguing their collections, not giving the way they were actually being used much consideration. It is fashionable to criticise GAFAM. But fortunately, Google, with its simplified menu and single search bar, has forced librarians to think about interoperability. Readers today need flexible and scalable environments where they can actually share content and manipulate it simultaneously. They expect content and tools that migrate from one device to another. People want to choose, combine and even create tools to build their own digital workbench. Therefore, libraries have been forced to reinvent themselves digitally and imagine new spaces to accommodate these new uses. But citizens are more than users. They each form a part of our communities. Librarians now participate in the construction of knowledge with their readers. But, above all, they are the original actors of a new civic commitment, taking advantage of the quality of the spaces they offer for free and their political neutrality.

1. End of a heliocentric system

The imagination of the Library of Alexandria, “Tous les savoirs du monde” (all the knowledge in the world) [1], is still alive today. It permeates the dreams of many librarians when they have to imagine a new space. They don’t count sheep as they go to sleep, but the sum of books neatly arranged on horizontal shelves, which leak into infinity. The library system for a long time was heliocentric. Each great library imagined itself to be the sun in a galaxy illuminated by other libraries that revolved around it. There was a time when the accumulation of books increased the force of attraction on readers. Throughout the 20th century, libraries were filled to overflowing. We, as librarians, then had to rent a lot of outdoor storage space to satisfy our infinite desire for centrality, an unconscious manifestation of our horror vacui.

Every morning the alarm clock of the Internet indicated that librarians were no longer at the centre of an ideal world. Each collection was incomplete, and none, however large, could claim to be exhaustive. It was a rude awakening. We also had to change our concept of ownership. We had to abandon this conception from the moment that owning did not allow us to obtain what we wanted, to be at the centre of the universe. As librarians, we suddenly had to become custodians, not possessors. What we had collected no longer belonged to us. We had to become the benevolent guardians of what history (i.e. other men and women) had entrusted to us.

This paradigm shift has had an extremely beneficial effect on the world of librarians. We no longer had to look at our navels, but at the libraries around us, and at the way visitors/readers wanted to search for information and combine it with that deposited in other libraries or places of knowledge.

librarians became custodians, not possessors - and just one satellite in a galaxy

Suddenly we were forced to work and think as a whole, constantly in motion, because we were no longer alone in controlling the thread of our growth. Librarians are no longer the only ones to master the organisation of knowledge. The Dewey system had run its course. We could keep it for convenience, but in reality, it was our readers who would increasingly be the actors of this trek, on paths to be cleared (or to be decoded).

The need for interoperability forced almost every library in the world to admit that it was just one satellite in a galaxy. Each library derived its uniqueness from its ability to communicate with other entities, and more importantly, to dialogue with its users.

2. The passer-through-walls

Giving a central role to the reader would shake things up. A reader is not an institution. He or she lives in real life, immersed in society. Previously, libraries lived in a vacuum in the world of knowledge. The intrusion of the reader into their growth process would have an unexpected consequence.

Like in French writer Marcel Aymé’s fantasy short story, the readers are a “Walker-through-walls"[2]. They take with them, or despite them, the whole intellectual atmosphere of their time. They are not formatted to think only within the established framework of places of knowledge. They bring the outside in. The ordinary social world bursts into the stifled world of libraries. The central issue is no longer the representation of knowledge, its organisation, or the symbolic power of library architecture: its façade. The passe-muraille does not care about the partitions and the antique columns. They inhabit the space where they wish to live and enjoy existence wholeheartedly, to the full. The “learning centres” that appeared in the 2000s were one of the manifestations of these open architectures, oriented towards learning and service, in a digital environment based on their appropriation by students.

Another consequence of these changes is the gradual transformation of the library from a place of knowledge to a space of knowledge [3]. Place of knowledge refers to an organisation in its entirety, which is embodied in an institution and asserts itself by its name: the school, the university, the library, etc. A space of knowledge is an in-between, where journeys are made, and relationships are forged.

In a place of knowledge, the reader asks the librarian what information he or she has on a particular author or subject. In a space of knowledge, the readers often come with an open question that is less about what exists than about how to express their question and carry out their research. The librarian accompanies the readers in their research, hand-in-hand.

The notion of place designates a location; geolocates it. Space, on the other hand, presupposes the expanse, the interval, the in-between that allows for mediation and the unforeseen.

from place of knowledge to space of knowledge, shaped by readers & societal concerns

The transformation of libraries that accept to be penetrated by the flow of digital networks shatters the notion of borders. And, even more than digitisation, it is the possibility of interrogating these digital resources with a natural language, which deconstructs the established order, and allows us to appropriate new territories. Like the American settlers taking possession of new territories, readers are not only inventing new ways of working, thinking and writing. They must inhabit the space, shape it, imagine new ways of doing things, in line with the concerns of the society in which they live.

3. Civic engagement

While UNESCO counts 95,000 museums worldwide, IFLA (The International Federation of Library Associations) estimates that there are 2.6 million libraries, of which more than 380,000 have internet access. The number, distribution and reputation for the neutrality of libraries make them ideal places to develop civic engagement projects. Libraries have become public places, freely accessible. We have seen above that they have evolved from an in-house approach to a community engagement approach over the last twenty years.

Complementary or contradictory forces are at work in these libraries. The architecture or the creation of new spaces allow for the experimentation of new relationships with the citizens who wish to inhabit these places. After letting the Passer-through-walls in the library, how would librarians turn their building into a platform for civic engagement? The observation made by many was that the advent of the Internet and social media has made people more insular. They now act more as spectators of the democratic process than as participants and interact less with people whose views do not match their own. Many projects are developed in libraries to break down individual "bubbles". I will mention four for example, but they could have been multiplied many times over.

community engagement projects to break down individual “bubbles”

The Chicago Community Trust's On the Table is an annual forum (on a single day) designed to bring people together to make good things happen. Libraries are one of the pillars of this event. People also gather in homes, offices, schools, restaurants or other spaces. They meet with others to share ideas and explore ways to improve the Chicago area. The results are new relationships, elevated civic conversations, and real pathways to collaborative action - outcomes that aim to make communities more connected, resilient, and resourceful. On the Table in Chicago (launched in 2014) has inspired similar initiatives in more than 30 communities nationally and internationally through the On the Table Network. The COVID pandemic has unfortunately interrupted this project since 2020.

The second example is Colombia. The country suffered 50 years of civil war. Many areas of the country where FARC fighters (Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia) lived have been ignored by the government for decades and lack everything. A national strategy has been launched to build sustainable relationships among the fractured population. A project has been developed with the NGO "Libraries without Borders," which has installed mobile libraries called Ideas Boxes, to reintegrate these ex-combatants into society and ensure a transition to civic life. As an NGO ran the project, it gave a semblance of neutrality that allowed the librarians and project managers to be accepted. The Ideas Box not only contained books but also connections to the Internet, other technologies and devices. It was also a new space that allowed group activities and informal exchanges that fostered social cohesion. After the young people, the adults came, interested in technical subjects (e.g. agriculture), attracted by this possibility of reinforcing their skills and reintegrating into society after the war years. The Ideas Boxes were extended by another mobile project, the "Muloteca", a makeshift library that the librarians built on the back of a mule to reach the most isolated areas. Through the "Muloteca", audiovisual workshops gave rise to several films in which former FARC members told their stories to help explain and demystify their community.

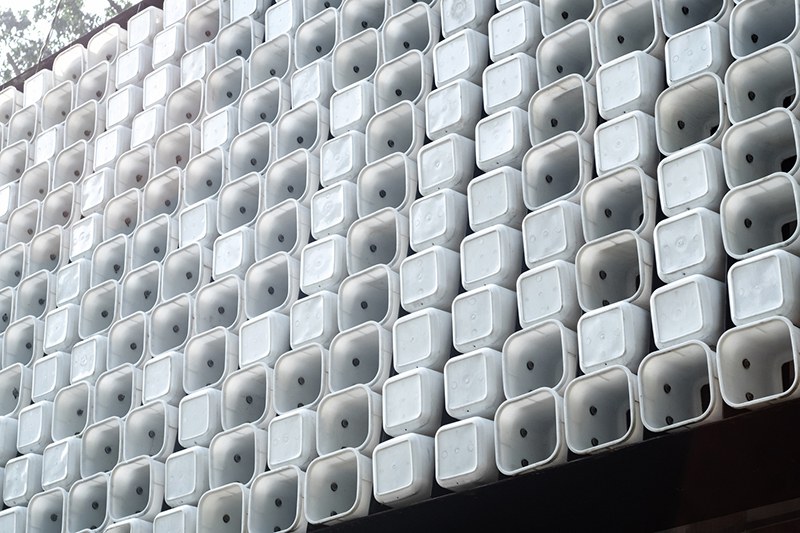

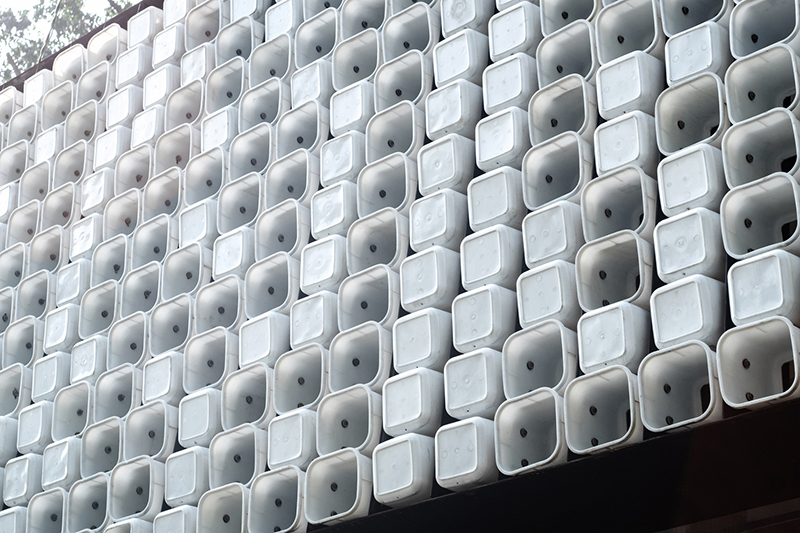

The idea of creating micro-libraries to invent spaces that allow the inhabitants of a place without the cultural infrastructure to come together is found in the prototype developed in Taman Bima, in Indonesia [4]. With the interest in books and reading declining in recent years, Indonesia's illiteracy and dropout rate remain high. The place is dedicated to reading and learning. The activities and teaching are currently supported and organised by Dompet Dhuafa (Pocket for the Poor) and the Indonesian Diaspora Foundation. However, the ultimate goal is to allow the local population to manage the content and maintenance independently.

The whole project was done at a low cost (35,000 euros). The architect (SHAU Architects, Bandung, Indonesia) took advantage of an existing square and improved its gathering capacity by shading it and protecting it from the rain. The building consists of a simple steel structure and concrete slabs. The interior does not use ventilation. To shade the interior, allowing sufficient ventilation, they had the idea of recovering 2000 used ice buckets that act as natural light bulbs and diffuse sunlight. Local craftsmen and artisans made the façade. The gathering effect on the square was multiplied by the idea of ‘floating the library’. The inhabitants gather underneath and around it. They benefit from the wifi connection without entering it. The important thing is not just to imagine the space between the walls but to create a beating heart that extends beyond the library space. After this project in 2016, a second micro-library was installed in Semarang in 2020.

In a completely different urban context, the predominantly white city of Seattle has a large immigrant population. Rising anti-Muslim and anti-immigrant sentiment has become a problem there, and the city has encouraged libraries to develop projects for immigrants and undocumented migrants. At the same time, the city wanted to engage the public in collective thinking about race and social justice. The Seattle Public Library created a Race and Social Justice Change Team in 2016, intending to transform how structural and institutional racism is addressed in the library. It led programmes such as 'American Visionaries', which featured a roster of immigrants giving personal testimonies celebrating the contributions of their communities, and 'Interrupting Whiteness', evenings of discussions on how white people can support racial justice .

4. Difficulties

The projects described above were all produced or supervised by civic engagement professionals. What difficulties are encountered by libraries that initiate this type of project alone [5]?

The point that systematically comes up is the lack of training of librarians for this type of action. This issue is at the heart of the concerns of the American Library Association (ALA), that developed the "Libraries Transforming Communities" initiative. It introduces libraries to different approaches to dialogue. The recordings of webinars designed to train library professionals are available on their website.

Conversely, a significant proportion of the people are unfamiliar with active public participation. This forces librarians to also take on the roles of motivators and educators. And it quickly raises the question of the relevance of the projects when they are not initiated by the grassroots and communities. There is no point in embarking on such civic engagement projects if there is no support from the people you address.

difficulties: staff training for new role / audience unfamiliar with active participation / balance with core function / neutrality

This type of engagement is not just another mediation activity before moving on to something else in the library's programming. In the example of the "Race and Social Justice programme" developed in Seattle to address homelessness and hunger, the library was overwhelmed by the demands of the public it had reached.

Initiating such projects means, for the library directors, first striking a balance between the core functions of the library (or considered to be so) concerning information development and the long-term management of these civic projects, and designing training programmes that allow librarians to participate in these initiatives with confidence. Libraries have to accept a new balance between central and local decision-making, with these new publics becoming partners in the institution. The library will need to ensure that it also accepts that the outcome of these projects may disrupt its programming.

Another problem is the concern of many librarians that they are overstepping their competence and identity as professionals. Ideally, the demand comes from the public, which makes the librarians' position more comfortable. To this end, librarians must be well integrated into the communities and that these new users should fully consider the library as a platform for them.

A final problematic aspect is the issue of neutrality. We have seen that the strength and reputation of libraries come from the perception that they are non-political spaces, which allow for the expression of all words and opinions. Libraries have often been refuges in times of trouble. However, these civic engagement projects quickly question this position of neutrality that is part of the strength of such institutions.

Libraries are part of the civic engagement ecosystem. Are they the best-prepared institutions to develop these projects alone? Is their strength not in their ability to create spaces for others to invent these projects? To pursue their existential transformation, which is to offer a platform of services that others will use, rather than trying to editorialise everything?

5. No more users

In 1999, the Idea Store in London shook up the library world . These buildings in the East End exemplified the "mash-up library" concept, which mixes many different services, with the need to introduce partner activities, with librarians being there to be facilitators, without themselves being responsible for all the services offered. However, they do provide information and mediation on these services. Extending the thinking of the Idea stores, the Nordic libraries have made a lot of noise in recent years in terms of innovation. One such example is the Dokk 1 library in Aarhus, Denmark . Inside the building, the spaces are divided into four types: inspiration room/learning room/meeting space/performative room (maker space, fab lab, etc. where you make and share). Several spaces were left entirely open for partners to take over and shape. Visitors are greeted by an interactive sound and visual installation when they enter the library. As in the past, in the chill-out rooms of the 1990s, adjacent to dance floors, filled with comfortable sofas and coloured lights, where one could listen to soothing background music, we need decompression breaks in libraries to find ourselves and others. A symbol of community life, the heart of the library is its 7.5m high gong. When a child is born in Aarhus, the parents are invited to press a button at the maternity hospital: then the gong sounds in the library. And all visitors/readers can then welcome this new citizen to the community.

Several Idea Stores in London have taken the (successful) gamble of being located inside shopping centres, blending into spaces that were alien to them but frequented by the public they wanted to reach. The Warrington Library in England, between Manchester and Liverpool, is located in a Hub, Great Sankey Neighbourhood Hub. The building includes several sports facilities (fitness, tennis, swimming pool). It is the first public building to receive the Gold Award from the Dementia Services Development Centre (DSDC) at the University of Stirling for its dementia-friendly architecture, design, and facilities. The library world has benefited from many years of reflection on the Third Place. They have learnt to work with subtlety on the atmosphere, to better welcome their visitors, who are made up of different individuals and communities. To achieve the Warrington Library's objective, it was particularly important to work on the colour dimension to make the space as welcoming as possible. As Daniela Hislop of Thedesignconcept team points out: "Colour has a physical and emotional impact on people and normally contributes to an interesting and inspiring environment. People with dementia often have vision problems, including poor depth perception and altered colour perception, which reduces their ability to perceive contrasts. Carpets, wall colours, fabrics, furniture and accessories are much brighter in daylight than in artificial light.” Over the last four or five years, museums have become increasingly fascinated with developing immersive experiences, creating new spaces of the mind. On the other hand, Libraries have been thinking more about the corporeal world to deepen the environmental perceptions through our five senses.

In the same spirit, the Muyinga library is an inclusive school for deaf children in Burundi [6]. This library aims to reconnect the deaf and blind community to the society from which they are excluded. The architectural process of making the library seeks to involve the broader community of Muyinga on behalf of these children. The library is coupled with a boarding school. In a second phase, the campus will incorporate a carpentry workshop at the school and a multi-purpose hall - projects that will serve the entire Muyinga community. The buildings are constructed materially by as many local people as possible so that they feel involved in the project. The construction forges the link, the bridge.

The library world is no exception to the "Bilbao effect". If the Muyinga library is designed to build a symbolic bridge between the community of deaf children and the society that rejects them, the Calgary library [7] in Canada is, literally, a bridge between two neighbourhoods: between the city's affluent downtown and the less prosperous area to the east. The library is part of a comprehensive urban plan in which $2 billion has been invested. Overlooking a railway line, Craig Dykers and the Norwegian-based architectural firm Snøhetta set out to build the $245 million central library, whose façade shines like a jewel. The building has four floors, 22,000 m2 of interior space and a podcast and YouTube video production studio. "Libraries are becoming increasingly diverse in what they offer," says the architect, "They offer space as well as information, and space is always a precious commodity in our society. In this sense, the library of the future is very similar to the library of the past." In the same spirit of providing more space, Snøhetta has just unveiled plans for a 16-metre-high glass library in Beijing, made up of pillars that create a canopy similar to a ginkgo forest. The interior will have an open, undulating floor plan of hill-like volumes.

This desire to create more and more free space, to vary the movements and scenes inside large libraries that become landscapes, can be seen in the Universitätsbibliothek Freiburg in Germany, built for "a digital future" [8]. Described as a polished diamond, it has become a landmark in the Freiburg cityscape. The interior design is very open; the library functions almost without interior walls. There is no large hall or representative foyer, making the entire space optimally usable and flexible and facilitating future development. The spaces are divided into a reading room for concentration and a "Parlatorium" (to give a little mediaeval touch) for communication. Architect Heinrich Degelo worked from a programme that set him three objectives: to create a place of learning, teaching and training. And, as a bonus, he had to offer an inspiring place. Like the Calgary library, a media centre (Medienzentrum) occupies an entire floor of 800 m2. Just as museums such as the Tate and the Met have become content producers since 2005, it has also become a trend for these large libraries to offer optimal content production, processing, and marketing conditions. The distribution of spaces must now include this aspect.

librarians have developed a sense of welcome & a subtle understanding of what a space for work, reflection and creation should be

"No more users", announced Tim Bray in 2010 [9]. Our readers and visitors are individuals, people. They need inspiring spaces to breathe and to meet. Librarians cannot do everything in the revolution they are going through, but they have developed a sense of welcome and a subtle understanding of what a space for work, reflection and creation should be. Some of them probably miss the time when the collection was the centre of their preoccupation, in an often solitary dialogue with the shadows. I, too, I confess, sometimes have this nostalgia. But it is a passing one because when I open my eyes, so many inspiring libraries have been created physically and virtually in the last 15 years. We are not quite here anymore and not quite there yet. We are on the road.

[1] The exhibition "Tous les savoirs du monde, encyclopédies et bibliothèques, de Sumer au XXIe siècle" was organised by the Bibliothèque nationale de France on the occasion of the opening of the François-Mitterrand site, from 17 December 1996 to 6 April 1997.

[2] For an English translation: https://stresscafe.com/translations/pm/index.htm.

[3] See Yi-Fu Tuan, Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience, University of Minnesota Press, 2021 (1977).

[4] Architects: SHAU Indonesia. Area : 160 m². Team : Florian Heinzelmann, Daliana Suryawinata, Yogi Ferdinand with Rizki Supratman, Roland Tejo Prayitno, Aditya Kusuma, Octavia Tunggal, Timmy Haryanto, Telesilla Bristogianni, Margaret Jo. Client : City of Bandung, Dompet Dhuafa. Contractor : Yogi Pribadi, Pramesti Sudjati. Supported By : Dompet Dhuafa, Urbane Community, Indonesian Diaspora Foundation. Signage Graphic Design : Nusae. Construction Costs : 35.000 Euro. City : Cicendo. Country : Indonesia.

[5] See Nancy Kranich, "Libraries and Civic Engagement », Library and Book Trade Almanac, 2012, p. 75-96. (https://scholarship.libraries.rutgers.edu/discovery/delivery/01RUT_INST:ResearchRepository/12643443320004646?l#13643534700004646) and Coward, C., McClay, C., Garrido, M. (2018). Public libraries as platforms for civic engagement. Seattle: Technology & Social Change Group, University of Washington Information School, 2018. https://digital.lib.washington.edu/researchworks/handle/1773/41877.

[6] Architects: BC Architects. Area: 140 m². Year: 2012. Local Material Consultancy : BC studies. Community Participation And Organisation : BC Studies and ODEDIM Muyinga. Cooperation : ODEDIM Muyinga NGO, Satimo Vzw, Sint-Lucas Architecture University, Sarolta Hüttl, Sebastiaan De Beir, Hanne Eckelmans. Financial Support : Satimo Vzw, Rotary Aalst, Zonta Brugge, Province Of West-Flanders. Budget : 40 000 €. City : Muyinga. Country : Burundi.

[7] Architects: Snøhetta. Area: 240000 ft². Year: 2018. Client : Calgary Municipal Land Corporation. Contractor : Stuart Olson. City: Calgary. Country: Canada.

[8] Architects: Degelo Architekten, Itten+Brechbühl. Area: 41673 m². Year: 2015. See Antje Kellersohn, "Die neue Universitätsbibliothek Freiburg – gebaut für eine digitale Zukunft", Bibliothek Forschung und Praxis, 40 Issue 3 (2016), p. 434-443. https://doi.org/10.1515/bfp-2016-0054.

[9] Timothy William Bray is a Canadian software developer, environmentalist, political activist and one of the co-authors of the original XML specification. Voir: https://www.tbray.org/ongoing/When/201x/2010/10/30/No-More-Users.

Acknowledgments

I would particularly like to thank Dr Charlotte Franson for her proofreading and comments, Michèle Antoine for her inspiring projects at Universcience and the colleagues with whom I had the pleasure of working at the Bibliothèque de Genève, the curators Jean-Phililippe Schmitt and Nicolas Schätti, whose work inspired many of the ideas in this text.

References

Bibliothèques en mouvement : innover, fonder, pratiquer de nouveaux espaces de savoir, ed. Yolande Maury, Susan Kovacs, Sylvie Condette, Villeneuve D'Ascq : Presses universitaires du Septentrion, 2018.

C. Coward, C. McClay, M. Garrido, Public libraries as platforms for civic engagement. Seattle: Technology & Social Change Group, University of Washington Information School, 2018.

Emy Nelson Decker and Seth M. Porter, Engaging design : creating libraries for modern users, Santa Barbara California : Libraries Unlimited, 2018.

Mary W. Elings, Günter Waibel. « Metadata for All: Descriptive Standards and Metadata Sharing across Libraries, Archives and Museums ». First Monday 12, no 3 (5 mars 2007).

Fred Schlipf, Constructing library buildings that work, Chicago : ALA Editions, 2020.

Luigi Failli. Du livre à la ville: la bibliothèque comme espace public. Genève: MétisPresses, 2017.

Peter Gisolfi, Collaborative library design : from planning to impact, Chicago : ALA Editions, 2018.

R. Thomas Hille, The new public library : design innovation for the twenty-first century, New York : Routledge Taylor & Francis Group, 2019.

Nancy Kranich, "Libraries and Civic Engagement », Library and Book Trade Almanac, 2012, p. 75-96. (https://scholarship.libraries.rutgers.edu/discovery/delivery/01RUT_INST:ResearchRepository/12643443320004646?l#13643534700004646)

Lynn D. Lampert, Coleen Meyers-Martin, Creating a learning commons : a practical guide for librarians, Lanham : Rowman & Littlefield, 2019.

Library design for the 21st century : collaborative strategies to ensure success, ed. Diane Koen and Traci Engel Lesneski, Berlin : De Gruyter Saur, 2019.

Spaces of culture and art, ed. Till Schröder, Fenna Tinnefeld, Christian Zillisch, Münster : Deutscher Architektur Verlag, 2018.

Yi-Fu Tuan, Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience, University of Minnesota Press, 2021 (1977).

Diane M. Zorich, , Günther Waibel, et Ricky Erway. Beyond the Silos of the LAMs: Collaboration Among Libraries, Archives, Museums. OCLC Research, 2008.